ALLENTOWN, Pa. — Pennsylvania’s current environmental justice policy does nothing to ensure that those most impacted by poor air quality, excessive heat and an aging housing stock will actually see positive change, Maria C. Ocasio said Thursday evening.

“Not only does the policy fail to carry the full force of law, but it also fails to impart litigation or, more importantly, denial for projects that will continue to place undue pollution pressure on already overburdened communities,” said Ocasio, Lehigh Valley field coordinator for Conservation Voters of PA and PennFuture. “We therefore call upon the [Department of Environmental Protection] to step it up in their protection for environmental justice communities, such as Allentown.”

Ocasio was one of about a dozen residents from the Lehigh Valley and beyond to attend the DEP’s last public comment meeting on the commonwealth’s interim environmental justice policy. Hosted at La Toxica Event Space, 1447 Lehigh Street, and lasting an hour, about half of those who attended provided feedback. While the majority said the policy doesn’t go far enough, one resident said there needs to be a balance between environmental justice initiatives and redevelopment.

Brian Evans, who described himself as a “lifelong resident of the Lehigh Valley,” said that while clean air, water and a safe environment are all important, he also remembers when industrial sites sat vacant across the region.

“We need to make sure that these regulations don't impede on that and prevent the redevelopment of these sites and encourage us to go back to the days of putting all of our new development out in green fields.”Brian Evans

“We need to make sure that we provide environmental justice, but we need to ensure that there's a balance that we don't put undue burden on the redevelopment of these formerly contaminated sites,” Evans said. “We need to make sure that these regulations don't impede on that and prevent the redevelopment of these sites and encourage us to go back to the days of putting all of our new development out in green fields.”

What is an environmental justice policy?

Adopted in mid-September, the DEP's interim final policy includes a working definition of environmental justice, arguing that it is “just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people … in agency decision-making and other activities that affect human health and the environment.”

With this framework in mind, the goal of the policy is to make sure all people “are fully protected from disproportionate and adverse human health and environmental effects (including risks) and hazards, including those related to climate change, the cumulative impacts of environmental and other burdens, and the legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers.”

"It’s also aimed at creating “equitable access to a healthy, sustainable and resilient environment in which to live, play, work, learn, grow, worship and engage in cultural and subsistence practices. It further involves the prevention of future environmental injustice and the redress of historic environmental injustice.”

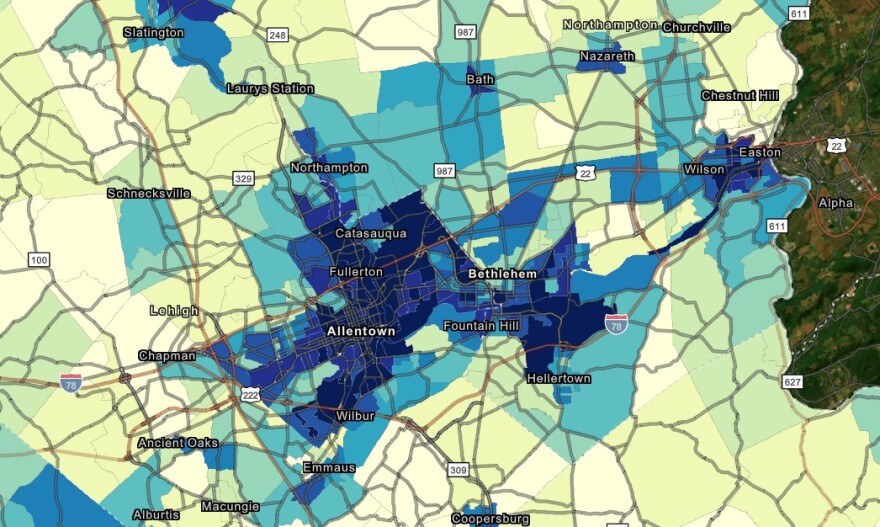

In order to find areas of the state experiencing inequity, officials created a system and mapping tool to highlight areas in need as an “EJ Area.” Those are census tracts in which 20% or more people live at or below the federal poverty line, and/or 30% or more identify as a non-white minority, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the federal guidelines.

Of the Lehigh Valley’s major cities, Allentown, Bethlehem, and Easton, all have tracts categorized as an Environmental Justice Area, according to PennEnviroScreen, the state’s mapping and screening tool.

Although the series of feedback meetings was announced in September, there were originally no in-person meetings slated for the Valley, even though the region is the third largest metropolitan area in the Commonwealth. The meeting in Allentown was added in late October.

‘This policy should go further’

Trevor Tormann, who represented Allentown's Department of Community and Economic Development, said the most burdened communities should be centered in the policy, and underscored the need for engagement, education and outreach in environmental justice communities.

“DEP grant dollars can catalyze capacity-building and harm reduction efforts within [environmental justice] communities,” Tormann said. “This policy should go further than providing preference for applications in EJ areas.”

He referenced President Joe Biden’s Justice40 initiative, which directs 40% of federal investments into environmental justice issues to disadvantaged communities.

“This is a just and measurable goal,” Tormann said. “ … When resources are distributed where they are needed most, EJ residents in the city of Allentown, and across Pennsylvania, will witness necessary improvements in their communities.”

While Sarah Opatovsky said she didn’t prepare remarks, she wanted to share a concept — “Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs,” a psychological theory proposed by Abraham Maslow in the mid-1940s. Food, water and shelter, the theory argues, are foundational to fulfilling needs.

"What I'm doing for Christmas doesn't matter. My 401K doesn't matter if I don't have safe food, clean water, clean air.”Sarah Opatovsky

“I just wanted to make a comment that what we're all doing here is some of the most important work anyone can do because it affects people's lives, affects not only the quality of life, but the length of their life,” she said. “ … What I'm doing for Christmas doesn't matter. My 401K doesn't matter if I don't have safe food, clean water, clean air.”

Approximately 500 comments have been received, a state official said after the meeting concluded. All comments were due just before midnight on Thursday.

During the first virtual public comment meeting, a Valley chemist voiced redlining concerns, arguing lenders or grantmakers shouldn’t be able to deny a resident or an organization based on their zip code.